T-7 To T-10 Transition

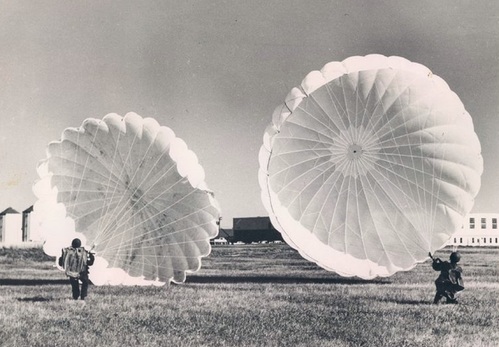

Comparison of T-7 & T-10 Canopies

Comparison of T-7 & T-10 Canopies

Although the parachutes developed during WWII provided a reliable, safe means of descent, the advent of the postwar higher speed airplanes, such as the C-119, meant jumping the T-7 style parachutes became hazardous. Plans for an improved troop parachute system were undertaken as far back as late 1944, but it would take a number of fatalities to hurry the adoption of improved equipment.

Between June 30, 1951, and June 30, 1952, twelve fatalities were traced directly to malfunctions of the T-7 parachute. These were largely due to the fact that the T-7 developed bugs when jumped at speeds ranging up to 150 knots. Tests showed that at 115 knots (130 MPH) or more, it was unreliable, had a dangerously severe opening shock, and caused excessive wear and tear. The slowest at which C-119 pilots flew consistently was 125 knots (145 MPH). A 1944 report indicated that even low speeds of 100 MPH could rip off holsters, canteens, and musette bags, and even snap the helmet weld. The additional speed of the postwar C-119’s meant bruises, severe riser burns, and even some broken shoulders.

Experimental XT-9 (Piggyback)

Experimental XT-9 (Piggyback)

The experimental model YT-8 was simply a modification of the T-7 with features of the Hart design, utilizing a notch in the rear of the canopy for steerability. Attempts to find a replacement with a slower rate of descent and better adapted to high speeds led to the XT-9. This static-line-operated prototype was a bag-deployed piggyback system, with the main chute on top and the reserve mounted immediately below it. While plans for the XT-9 went back to April 1946, the first tests were not made until July 1950. Although the Quartermaster Corps hoped to purchase the improved XT-9 parachute, it was unknown as to when the final tests would be completed, and the mobilization requirements were yet to be filled. As the T-7 was a proven parachute, it was decided that contracts for $12,000,000 worth of T-7s, should be signed immediately and a small number of XT-9s be procured only for field tests.

Shortly thereafter, the XT-10 entered the scene and testing began in February 1951 and was released in October; soon all thought of the XT-9 was abandoned. Switlik Parachute Company’s chief engineer Harold J. Moran designed the 35’ parabolic T-10 canopy in 1949, and a patent was assigned in early 1950. The canopy was essentially a 28’ flat circular chute with an extended skirt, 30 suspension lines, and constructed with the new 1.1 ounce ripstop nylon. The nylon harness remained the same as the T-7 with the exception of separable connector links and Capewell shoulder releases on the risers. The Capewell release was designed by Alden Y. Warner and Wilbur J. Craven in 1947 and was accepted by the army in 1950 after a mass jump with T-7s in Lexington, Kentucky, where several paratroopers were dragged to their deaths, unable to jettison their canopies.

Shortly thereafter, the XT-10 entered the scene and testing began in February 1951 and was released in October; soon all thought of the XT-9 was abandoned. Switlik Parachute Company’s chief engineer Harold J. Moran designed the 35’ parabolic T-10 canopy in 1949, and a patent was assigned in early 1950. The canopy was essentially a 28’ flat circular chute with an extended skirt, 30 suspension lines, and constructed with the new 1.1 ounce ripstop nylon. The nylon harness remained the same as the T-7 with the exception of separable connector links and Capewell shoulder releases on the risers. The Capewell release was designed by Alden Y. Warner and Wilbur J. Craven in 1947 and was accepted by the army in 1950 after a mass jump with T-7s in Lexington, Kentucky, where several paratroopers were dragged to their deaths, unable to jettison their canopies.

Artist's Rendition of the T-10 Opening Shock

Artist's Rendition of the T-10 Opening Shock

During descent, the XT-10 oscillated considerably less, and its rate of descent was 4 fps slower than the T-7 when dropped with a 225 pound load. Most importantly, it reduced the parachute opening shock and improved reliability, giving the wearer less shock at 150 knots (170 MPH) than the T-7 at 115 knots (130 MPH). The XT-10 had enhanced reliability at speeds of 100-150 knots (115-170 MPH), and during a series of 6,500 test drops, no malfunctions serious enough to require activation of the reserve were encountered. There were, however, some wearers of the coveted parachute wings who referred to the T-10 as an “old man’s” or “staff officer’s” chute because it came down so easily that the thrill was gone. But the spokesman for those in favor of the T-10 said, “We like to let the old men down easy, but we like to let the young lads down easy too, who are carrying everything but the kitchen sink.”

The T-10 was standardized in October 1952, but procurement of the parachute was delayed; 107,981 T-7 parachutes, valued at approximately $25,000,000 were in the system as late as February 18, 1953, of which $12,000,000 were only recently purchased. Despite the obvious advantages of the T-10, some in authority thought that for reasons of economy, the stocks of T-7s should be used up before the T-10 was adopted. This would take either 8-1/2 years or 100 jumps per chute. However, according to Colonel Malloy, that although this "is the same policy that applies to most of our other items of equipment… his life depends on this parachute a whole lot more. When we develop a new type of medicine, if it is proven that it will save more lives, we don’t continue to use old stocks until we use them up. We start procuring it right now."

In February 1953, regardless of cost, the immediate procurement and issue of the T-10 was ordered. Through excellent cooperation of the Air Force, all necessary procedures were completed by March 26, 1953, and the purchase directives for 53,000 T-10s were furnished and the final awards of contract were to take place before May 15. Through the combined efforts of the Quartermaster Corps and the Air Force, an accelerated delivery schedule was set up in which the first 1,000 T-10s arrived in August of 1953. By March 1954, Reliance Manufacturing Company manufactured 30,000 T-10s, Alamo Manufacturing Company 13, 124, and Sigmund Eisner Company 10,000, for a grand total of 53,124 T-10s.

In an effort to recoup part of the $190 for a T-10 assembly, stocks of T-7s were converted to T-10s by utilizing the T-7 harness and pack tray and procuring only the T-10 canopy and deployment bag at a cost of $130. Small extensions where added to the T-7 pack tray to encapsulate the larger canopy; the steel frame, suspension line retainers, and riser tabs were removed, and new snap-on harness retainers were attached. This conversion left many T-7 28’ canopies that still had a useful lifespan. In 1951, the 82nd Airborne Division conceived the idea of converting T-7 troop parachutes into cargo use in an effort to accelerate the phasing out of the T-7. Jeffersonville Depot converted 23,359 of the remaining T-7 parachutes in the system starting in June of 1952. It was predicted that cargo parachute requirements for Korean, training, and mobilization reserves would absorb the majority of T-7 canopies left over from the conversion to the T-10. These conversions saved the army a total of $12,830,510.

By the end of 1954, the T-7 was almost completely phased out and replaced by the T-10. Between October 1953 and January 1954, 12,000 T-10 jumps were accomplished by the XVIII Airborne Corps with no fatalities and a negligible number of injuries. The T-10 soldiered on with several modifications for another 50 years, having been only recently replaced by the T-11.

The T-10 was standardized in October 1952, but procurement of the parachute was delayed; 107,981 T-7 parachutes, valued at approximately $25,000,000 were in the system as late as February 18, 1953, of which $12,000,000 were only recently purchased. Despite the obvious advantages of the T-10, some in authority thought that for reasons of economy, the stocks of T-7s should be used up before the T-10 was adopted. This would take either 8-1/2 years or 100 jumps per chute. However, according to Colonel Malloy, that although this "is the same policy that applies to most of our other items of equipment… his life depends on this parachute a whole lot more. When we develop a new type of medicine, if it is proven that it will save more lives, we don’t continue to use old stocks until we use them up. We start procuring it right now."

In February 1953, regardless of cost, the immediate procurement and issue of the T-10 was ordered. Through excellent cooperation of the Air Force, all necessary procedures were completed by March 26, 1953, and the purchase directives for 53,000 T-10s were furnished and the final awards of contract were to take place before May 15. Through the combined efforts of the Quartermaster Corps and the Air Force, an accelerated delivery schedule was set up in which the first 1,000 T-10s arrived in August of 1953. By March 1954, Reliance Manufacturing Company manufactured 30,000 T-10s, Alamo Manufacturing Company 13, 124, and Sigmund Eisner Company 10,000, for a grand total of 53,124 T-10s.

In an effort to recoup part of the $190 for a T-10 assembly, stocks of T-7s were converted to T-10s by utilizing the T-7 harness and pack tray and procuring only the T-10 canopy and deployment bag at a cost of $130. Small extensions where added to the T-7 pack tray to encapsulate the larger canopy; the steel frame, suspension line retainers, and riser tabs were removed, and new snap-on harness retainers were attached. This conversion left many T-7 28’ canopies that still had a useful lifespan. In 1951, the 82nd Airborne Division conceived the idea of converting T-7 troop parachutes into cargo use in an effort to accelerate the phasing out of the T-7. Jeffersonville Depot converted 23,359 of the remaining T-7 parachutes in the system starting in June of 1952. It was predicted that cargo parachute requirements for Korean, training, and mobilization reserves would absorb the majority of T-7 canopies left over from the conversion to the T-10. These conversions saved the army a total of $12,830,510.

By the end of 1954, the T-7 was almost completely phased out and replaced by the T-10. Between October 1953 and January 1954, 12,000 T-10 jumps were accomplished by the XVIII Airborne Corps with no fatalities and a negligible number of injuries. The T-10 soldiered on with several modifications for another 50 years, having been only recently replaced by the T-11.